Before you continue...

Be prepared to think. I want to make you think. And then I want you to post your thoughts as comments below the blog posts. If anything I write confuses you, please ask questions. Questions are a very effective way to get answers.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Experiments in Learning

Classical conditioning in all it's forms can get pretty complicated and philosophical if you let it. For example, I want to know why the absence of an introduced stimulus could not be a stimulus in itself. I'm going to anticipate some confusion here and explain a little of the experimental circumstances in which this would be an issue. Consider a classical conditioning experiment in which an electrical shock is paired with a click. First the subject hears the click, then the subject is zapped. The subject learns very quickly that the click precedes the shock. Thus when the subject hears the click, he/she prepares to be shocked (by cringing or other fear responses). Suppose I introduce a new click, one a little higher or lower in pitch than the first. This encourages the subject to generalize the click stimulus to any click stimulus. After the subject has learned that both clicks precede a shock (determined by measuring the fear response to each click before the shock is administered), I introduce a third click sound that is not followed by a shock. This is essentially the discrimination experiment design, with the added encouragement to generalize. At first, the subject is likely to exhibit a fear response to the third sound because it is similar to the other two. However, the absence of the shock is a new experience. If we are talking to strictly behavioral psychologists, I mean experience in the Kantian sense of a physical sensation. This lack of physical stimulus (shock) then becomes associated with the third click sound, discriminated from the other two. The fear response declines as trials continue, similar to the extinction experimental design, but specifically associated with the third click sound. This process of discrimination was cited as evidence against the temporal contiguity 'law' of association on the grounds that the absence of a stimulus is not a stimulus and no association can be formed.

Consider a temporal conditioning design in which the presentation of reinforcement occurs at regular intervals. One could say that the presentation of the reinforcement is paired with the passage of time, exactly like standard classical conditioning. The conditioned stimulus is considered to be the passage of time, not the presentation of another stimulus. Regular classical conditioning relies on an inter-stimulus interval to be effective. Simultaneous presentation of stimuli does not produce associative learning. This inter-stimulus interval (ISI) can be treated similarly to temporal conditioning with a potentially confounding addition of another stimulus. Since an optimal ISI can be measured for each species and I imagine, each individual, I can say that there is a loosely fixed time period in which an association can form. I can even imagine an experimental design that can tease out increased effectiveness and accuracy in temporal conditioning by spacing reinforcements in increments of this optimal ISI. Regardless of whether that would work, the association between ISI and associative learning effectiveness is relatively well understood. A classical conditioning experiment tuned to the optimal ISI is more effective than one that is not so tuned. By extrapolation, it is easy to think of the optimal ISI as an event zone, which is the major point of contention against the absence of a stimulus. The absence of a stimulus can now be measured as an event with respect to the optimal ISI.

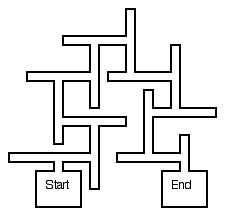

I should note here, that extinction and discrimination are an inhibitory design, where the conditioned stimulus is predictive of an absence of the unconditioned stimulus. Supposedly an inhibitory design cannot take place without prior associative conditioning. However, I have designed an experiment to test this (and was yelled at by students in class for contradicting the professor). My experiment isolates the effect without any prior associative conditioning. One would need a maze big enough to randomly place roughly one hundred reinforcements in two or three hundred different position. As a rat moves through the maze, it may discover these. It would be allowed to eat some of them (assuming the reinforcements are food) but upon discovering others, a buzzer would sound and the food would be taken away. If by the end of the test the rat ignores food when the buzzer sounds without having to actually remove the food, inhibitory conditioning will have taken place. Very simple, just requires a very large maze similar in design to the one below.

For more general cases of learning, some new research shows that attitudes toward learning are extremely influential on learning outcomes. Someone who believes learning is an acquisition of skills through error and effort will learn faster than someone in a fixed frame of mind. The complexities involved in self image and attitude are not explicitly addressed in the study but are implied as affecting learning outcomes in a greater proportion to what was commonly believed to be the case. One example if this relationship which I have written about before is how a single word choice can affect the attitude and thus the learning of an individual or class of students. If the teacher tells the class that they are about to cover the "hard" part of a subject, the students form an expectation that it will be difficult and are likely to react defensively to the presentation. That is, with an expected difficulty, the students exhibit a fear response which inhibits learning by causing them to dwell on each little aspect of it, questioning their understanding and overshadowing subsequent information with worries about previous information. On the other hand, if the teacher tells the students that they are approaching the "fun" part of a subject, the students will react with increased interest and anticipation of pleasurable experiences. The study finds that when a student is led to believe that their success is due to effort (one simple sentence of praise to this effect is enough), the students will rise to further challenges able to correct past mistakes and even excel at tasks designed for much older students, given the chance to learn from said mistakes. Those told that their success is a function of their intrinsic intelligence will avoid challenges in order to avoid mistakes altogether, ostensibly to appear smarter by percentage.

I would like to remind folks that if I am told that something is impossible, I will immediately set out to find a case to the contrary. Nearly anything presented in absolute terms can be proven innaccurate with a single counterexample. As such, I will take it as a personal challenge to find that exception. Don't follow the rules over a cliff.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

More Classroom Frustrations

Today I was told in no uncertain terms that my questions are unwelcome in class. They're unwelcome because they represent a type of thinking that many of the other students are unwilling to do. I'm not sure what that means. I'm really confused about being told that these other students don't want to think for themselves, they want to absorb and regurgitate the material of the class. The Prof attempts to encourage thinking by asking these students to choose between opposing theories after presenting evidence that the theories are not opposed, but work together in different parts of the brain. This evidence is based on physiological studies that were not available at the time the opposed theories were originally formulated. While I understand the merits of asking students to distinguish between ideas and point out the strengths and weaknesses of each, the flaw in the method is that by presenting two choices as mutually exclusive and holistic (without any third theories available) the students are likely to neglect other options. Evidence of separate processes that follow the model set forth by both theories does nothing to help this; it only invites a rejection of sound scientific findings. It seems that once again my expectations and standards are laughably high. Intellectual discourse and critical thinking are frowned upon in upper division courses.

I am required to take this course, if I want to complete a degree in psychology at this university. I want to complete my degree. I have to stay at this university because it's affordable and I'm nearly finished anyway. That said, I will not drop the course as one student kindly pointed out I may do. Everyone in the course is paying for it, myself included. Thus arguments to the effect that they have rights to uninterrupted lecture because they are paying for it are moot. I am paying the college to provide me time to pick a particular professor's brain about a particular subject. That implies that I can reasonably expect an answer to questions I have about the course material. If the professor acknowledges my question and spends class time to answer, that is at her discretion. If the professor wishes to complete the lecture and discuss my question outside of class, that is also at her discretion. I am unaware of any rule that states I may not "interrupt" another's learning by asking a question. I also know of no rule that says the other students have the right to shout down both myself and the professor so that the professor will continue the lecture. At the same time, however, I don't know of any rule that says they can't. In addition to all of this, I am fully aware that there is no consensus concerning the value of my questions among the students. Some appreciate the depth added to the content, and others despise that I would even think to ask questions during a boring lecture. Because of these mixed signals, I am inclined to satisfy my own curiosity until such time as the professor takes control of the situation and decides that either I or the noisy students need to shut up. As long as the professor is answering my questions, I will not stop asking.

I realize that my thought patterns are not common. Not everyone goes around relating every little thing they learn to every other thing they have ever learned. That doesn't mean that the process is somehow invalid or intrinsically less valuable. It doesn't even mean that my thoughts are intrinsically more valuable. What it does mean is that I will ask questions to help me more accurately relate concepts to each other and point out any inconsistencies I discover so that I may resolve them. I think of my belief system, everything I know, as a vast web of connections between data points. The more connections, the stronger a data point will be, and the easier it is to remember. When a connection is found to be false, or weak, it must be replaced with a new or stronger one in order to keep the structure from collapsing. Compare this to building a house of cards. People who do this for fun have likely discovered that packing three or four cards together make better walls. If each card is a belief, the other beliefs around it rely on it for support. If one slips out, a whole section of the house falls. If one notices a weakness in the structure, repairing that weakness strengthens the structure and makes it less likely to fall. A new belief, or fresh concept, is like placing one card at the top of the house. It needs another card to hold it up, such as an association with another similar concept or an understanding of what makes the concept work. If the base is weak, or there are no supporting concepts, the idea falls. You cannot teach a child to add when it cannot yet count. A child cannot add large numbers if it cannot count high enough. Thus, by actively associating new concepts with as many old ones around it as I can, I ensure that the new do not crumble as readily. In short, this method of constant association with things is what allows me to go through classes without taking notes, even to the point of correctly anticipating new concepts I have not yet explicitly learned. There is a reason I was the designated test taker for my high school DECA team.

In higher learning institutions, I expected to find attitudes more encouraging of self-challenge and deeper understanding of topics. I was led to believe that the antics of high school were to be left behind in high school so that those interested in learning a topic in depth could be free to do so. Apparently, that belief is wrong, at least in the case of the institution I am now attending. I am continually told to go somewhere else to find the quality of learning I am looking for while simultaneously I am to believe that the education I am paying for is effectively preparing me for even higher learning of more specific types of knowledge. How can I reasonably expect to be prepared for things which are actively discouraged (mostly by other students)? I am treated as a miscreant for thinking in ways I was led to believe were encouraged in upper division courses, especially in the sciences. How can I reconcile these beliefs? Which walls do I tear down to strengthen this feeble house of cards? If I allow myself to slip into passivity I relinquish hope of becoming and effective researcher. If I continue to antagonize the other students I risk ostracism, poor grades, and even violence if other's views are taken to extremes. I would prefer not to risk my grade, but I seem to do so in both cases for I have discovered that my most effective means of learning is taking an active role in class. Another self discovery is that if I don't take care of ideas as I have them, they become forgotten. Often these ideas are irrecoverable or irrelevant upon remembrance. Contrary to popular belief, if my assessment of it is correct, I am a very considerate person and would prefer not to disrupt the learning of others. At the same time, how can I be expected to disrupt my own optimal learning pattern? I firmly believe that the questions I ask in classes are mirrors of questions that other students do not voice or have otherwise not thought of, which enhances the learning of those around me. I have specific examples of evidence to support this belief. At the same time, some students which have a hard time digesting the class material are clearly further confused by my inquiries into more complex areas. Thus I am torn between continuing as I am to enhance my own and other's learning or ceasing my active role in class to accede to the demands of the vocal objectors to my activity. Once again, given the more or less balanced nature of the options, I am forced to conclude that it is better for me to act in my own interest rather than throw in the towel. I am willing to fight for my own edification, even if others are not willing to take charge of their own.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)