Before you continue...

Be prepared to think. I want to make you think. And then I want you to post your thoughts as comments below the blog posts. If anything I write confuses you, please ask questions. Questions are a very effective way to get answers.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Experiments in Learning

Classical conditioning in all it's forms can get pretty complicated and philosophical if you let it. For example, I want to know why the absence of an introduced stimulus could not be a stimulus in itself. I'm going to anticipate some confusion here and explain a little of the experimental circumstances in which this would be an issue. Consider a classical conditioning experiment in which an electrical shock is paired with a click. First the subject hears the click, then the subject is zapped. The subject learns very quickly that the click precedes the shock. Thus when the subject hears the click, he/she prepares to be shocked (by cringing or other fear responses). Suppose I introduce a new click, one a little higher or lower in pitch than the first. This encourages the subject to generalize the click stimulus to any click stimulus. After the subject has learned that both clicks precede a shock (determined by measuring the fear response to each click before the shock is administered), I introduce a third click sound that is not followed by a shock. This is essentially the discrimination experiment design, with the added encouragement to generalize. At first, the subject is likely to exhibit a fear response to the third sound because it is similar to the other two. However, the absence of the shock is a new experience. If we are talking to strictly behavioral psychologists, I mean experience in the Kantian sense of a physical sensation. This lack of physical stimulus (shock) then becomes associated with the third click sound, discriminated from the other two. The fear response declines as trials continue, similar to the extinction experimental design, but specifically associated with the third click sound. This process of discrimination was cited as evidence against the temporal contiguity 'law' of association on the grounds that the absence of a stimulus is not a stimulus and no association can be formed.

Consider a temporal conditioning design in which the presentation of reinforcement occurs at regular intervals. One could say that the presentation of the reinforcement is paired with the passage of time, exactly like standard classical conditioning. The conditioned stimulus is considered to be the passage of time, not the presentation of another stimulus. Regular classical conditioning relies on an inter-stimulus interval to be effective. Simultaneous presentation of stimuli does not produce associative learning. This inter-stimulus interval (ISI) can be treated similarly to temporal conditioning with a potentially confounding addition of another stimulus. Since an optimal ISI can be measured for each species and I imagine, each individual, I can say that there is a loosely fixed time period in which an association can form. I can even imagine an experimental design that can tease out increased effectiveness and accuracy in temporal conditioning by spacing reinforcements in increments of this optimal ISI. Regardless of whether that would work, the association between ISI and associative learning effectiveness is relatively well understood. A classical conditioning experiment tuned to the optimal ISI is more effective than one that is not so tuned. By extrapolation, it is easy to think of the optimal ISI as an event zone, which is the major point of contention against the absence of a stimulus. The absence of a stimulus can now be measured as an event with respect to the optimal ISI.

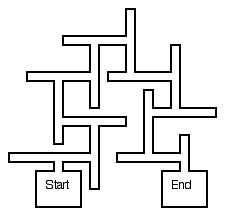

I should note here, that extinction and discrimination are an inhibitory design, where the conditioned stimulus is predictive of an absence of the unconditioned stimulus. Supposedly an inhibitory design cannot take place without prior associative conditioning. However, I have designed an experiment to test this (and was yelled at by students in class for contradicting the professor). My experiment isolates the effect without any prior associative conditioning. One would need a maze big enough to randomly place roughly one hundred reinforcements in two or three hundred different position. As a rat moves through the maze, it may discover these. It would be allowed to eat some of them (assuming the reinforcements are food) but upon discovering others, a buzzer would sound and the food would be taken away. If by the end of the test the rat ignores food when the buzzer sounds without having to actually remove the food, inhibitory conditioning will have taken place. Very simple, just requires a very large maze similar in design to the one below.

For more general cases of learning, some new research shows that attitudes toward learning are extremely influential on learning outcomes. Someone who believes learning is an acquisition of skills through error and effort will learn faster than someone in a fixed frame of mind. The complexities involved in self image and attitude are not explicitly addressed in the study but are implied as affecting learning outcomes in a greater proportion to what was commonly believed to be the case. One example if this relationship which I have written about before is how a single word choice can affect the attitude and thus the learning of an individual or class of students. If the teacher tells the class that they are about to cover the "hard" part of a subject, the students form an expectation that it will be difficult and are likely to react defensively to the presentation. That is, with an expected difficulty, the students exhibit a fear response which inhibits learning by causing them to dwell on each little aspect of it, questioning their understanding and overshadowing subsequent information with worries about previous information. On the other hand, if the teacher tells the students that they are approaching the "fun" part of a subject, the students will react with increased interest and anticipation of pleasurable experiences. The study finds that when a student is led to believe that their success is due to effort (one simple sentence of praise to this effect is enough), the students will rise to further challenges able to correct past mistakes and even excel at tasks designed for much older students, given the chance to learn from said mistakes. Those told that their success is a function of their intrinsic intelligence will avoid challenges in order to avoid mistakes altogether, ostensibly to appear smarter by percentage.

I would like to remind folks that if I am told that something is impossible, I will immediately set out to find a case to the contrary. Nearly anything presented in absolute terms can be proven innaccurate with a single counterexample. As such, I will take it as a personal challenge to find that exception. Don't follow the rules over a cliff.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Post your thoughts here.